Rocky Mountain

National Park

Colorado

breathtaking landscapes with towering peaks, alpine meadows, and diverse wildlife

Fast Facts

Location

Colorado

Established in

1915

Established by

President Woodrow Wilson

Size

415 sq. miles

Known For

- Rocky Mountain National Park is renowned for its stunning mountainous landscapes

- The park is home to a unique alpine tundra ecosystem, where hardy plants and wildlife have adapted to the harsh conditions of high elevations

- Various outdoor activities, such as camping, fishing, rock climbing, and snowshoeing

History

Natural History and Formation

The formation of the Rocky Mountains is a complex geological process that unfolded over millions of years. The Rockies are part of the larger system of mountain ranges known as the Cordillera, which extends from the southern tip of South America to the northernmost reaches of North America.

Precambrian Era: The origins of the Rocky Mountains date back to the Precambrian era, over a billion years ago. During this time, tectonic activity caused the formation of ancient rocks and the initial uplift of what would later become the foundation for the Rockies.

Laramide Orogeny (Late Cretaceous to Eocene): The most significant tectonic event in the formation of the Rockies was the Laramide Orogeny, which occurred roughly 70 to 40 million years ago. During this period, the Farallon Plate subducted beneath the North American Plate, leading to intense mountain-building activity. The uplifting of the Earth’s crust resulted in the formation of large mountain ranges, including the ancestral Rocky Mountains.

Erosion and Uplift: Over millions of years, the Rockies experienced cycles of uplift and erosion. The forces of erosion, driven by wind, water, and ice, gradually wore down the mountains. Simultaneously, tectonic forces continued to uplift the region, maintaining the overall elevation of the Rockies.

Ice Ages and Glaciation: During the Pleistocene Epoch, which began around 2.6 million years ago, the Rocky Mountains were further shaped by glacial activity. Ice sheets and glaciers carved out valleys and shaped the landscape, contributing to the rugged terrain seen today.

Modern Landscape: The ongoing geological processes, including tectonic activity and erosion, continue to shape the Rockies. While the Laramide Orogeny played a crucial role in their initial formation, the dynamic interplay of various geological forces has contributed to the diverse and majestic landscape of the Rocky Mountains that we see today.

Native History

The region that is now Rocky Mountain National Park has a rich Native American history, with evidence of human presence dating back thousands of years. Several Native American tribes have historical and cultural connections to this area, and their stories are an integral part of the park’s history.

Archaic Period: Archaeological evidence suggests that Native American groups have been present in the region for at least 10,000 years. During the Archaic period, these early inhabitants engaged in hunting, gathering, and later, small-scale agriculture.

Ute Tribe: The Ute people are one of the indigenous groups historically associated with the Rocky Mountain region, including the area that is now the national park. The Ute were nomadic hunter-gatherers who followed the seasonal migration patterns of wildlife in the mountains.

Summer Encampments: Native American groups, including the Ute, often used the high mountain areas of what is now Rocky Mountain National Park as summer encampments. The abundant natural resources in the region provided them with an opportunity to gather plants, hunt game, and engage in cultural practices.

Trade and Interaction: Native American groups engaged in trade and cultural exchange with neighboring tribes. The park’s location made it a crossroads for various tribal interactions, contributing to the rich cultural tapestry of the region.

Euro-American Contact: With the arrival of European settlers and explorers in the 19th century, the lives of Native American communities in the Rocky Mountain region were significantly impacted. The Ute and other tribes faced challenges as European-Americans encroached on their traditional lands.

Homesteading and Reservation Period: As the U.S. government implemented policies such as homesteading and the establishment of reservations, Native American communities were often displaced from their ancestral lands. The Ute people, in particular, faced significant changes to their way of life during this period.

Cultural Significance: The mountains and landscapes of Rocky Mountain National Park have cultural and spiritual significance for Native American tribes. Many of the natural features hold traditional stories and are considered sacred.

While the Native American presence in the park’s history is significant, it’s essential to recognize that European-American expansion and policies have had lasting impacts on indigenous communities in the region. Today, efforts are made to acknowledge and respect the cultural heritage of Native American tribes connected to Rocky Mountain National Park. Interpretive programs and materials within the park often highlight the contributions and history of Native American communities in the area.

Preservation

The preservation history of Rocky Mountain National Park reflects a broader movement in the United States to conserve and protect natural landscapes for future generations.

Early Advocacy: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, individuals such as Enos Mills, a naturalist and nature guide, played a crucial role in advocating for the protection of the Rocky Mountains. Mills lobbied for the establishment of a national park to preserve the pristine wilderness and scenic beauty of the region.

Enabling Legislation: On January 26, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Rocky Mountain National Park Act, officially establishing the park. The legislation aimed to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein” and marked a significant step in the preservation movement.

Early Challenges: In the early years, the park faced challenges, including insufficient funding and development pressures. Efforts were made to balance the preservation of the natural environment with the growing interest in recreational use.

Mission Expansion: Over the years, the mission of the National Park Service evolved to not only preserve the natural beauty but also to provide for the enjoyment of the park by the public. This dual mission, emphasizing conservation and recreation, became a hallmark of the National Park Service.

Infrastructure Development: In the following decades, the National Park Service invested in infrastructure development within the park. This included the construction of roads, trails, and visitor facilities to make the park accessible while carefully managing the impact on the environment.

Wilderness Designation: In 1976, a significant portion of Rocky Mountain National Park was designated as wilderness, providing an added layer of protection to the park’s most pristine and untouched areas. Wilderness designation restricts certain human activities and ensures that these areas remain in a natural state.

The preservation history of Rocky Mountain National Park reflects a commitment to conserving the natural and cultural heritage of the region while allowing for responsible public enjoyment. It showcases the evolution of conservation ideals and practices within the broader context of the National Park Service’s mission to preserve and protect America’s natural treasures.

Future Preservation

Preserving Rocky Mountain National Park for the future involves addressing various challenges, ranging from environmental concerns to managing human impact.

Temperature Changes: Warmer temperatures are a key aspect of climate change, and this can have widespread effects in the Rockies. Higher temperatures can alter the timing of seasonal events, such as the timing of snowmelt, plant flowering, and animal migrations.

Glacial Melting: The Rocky Mountains are home to glaciers, and rising temperatures contribute to their melting. This affects water availability downstream, impacting both aquatic ecosystems and water resources for human use.

Snowpack Reduction: Changes in precipitation patterns and warmer temperatures can lead to a reduction in snowpack, which is critical for providing water to rivers and streams during the spring and summer months. This has implications for both the park’s ecosystems and downstream water users.

Vegetation Shifts: Changing temperature and precipitation patterns can influence the distribution of plant species in the park. Lower-elevation species may move upslope, potentially impacting the composition and structure of plant communities.

Wildlife Habitat Changes: As vegetation shifts, the habitats for wildlife may also change. Species that are adapted to specific temperature and vegetation conditions may need to adapt or migrate to find suitable habitats.

Altered Fire Regimes: Warmer and drier conditions can influence the frequency and intensity of wildfires. Changes in fire regimes can impact the composition of plant communities and pose challenges for both wildlife and human safety.

Water Resources: Changes in snowpack and glacial melting can affect the availability and timing of water resources. This has implications for both aquatic ecosystems within the park and downstream water users, including agriculture and urban areas.

Biodiversity Conservation: Maintaining biodiversity is crucial for the health of ecosystems in the park. Challenges include protecting rare and endangered species, addressing invasive species that can threaten native flora and fauna, and managing the impact of human activities on wildlife habitats.

Visitor Management: The park attracts a large number of visitors each year, and managing their impact is a continual challenge. Issues include trail erosion, wildlife disturbance, waste management, and balancing the desire for recreational access with the need to protect sensitive areas.

Cultural Heritage Protection: Protecting the cultural and historical resources within the park, including Native American archaeological sites, is essential. This involves balancing the preservation of these resources with public access and education.

Addressing these challenges requires a holistic and adaptive approach, combining scientific research, public engagement, and sustainable management practices. The goal is to balance the preservation of Rocky Mountain National Park’s natural and cultural resources with the needs and expectations of present and future generations.

Geography

Rocky Mountain National Park, nestled in the heart of the Colorado Rockies, showcases a stunning landscape defined by its towering peaks, alpine meadows, and glacial valleys. The park’s geography is characterized by its rugged terrain, including 77 named peaks over 12,000 feet in elevation, as well as numerous lakes, rivers, and waterfalls. With its diverse ecosystems, dramatic scenery, and abundant wildlife, Rocky Mountain National Park offers visitors an unparalleled opportunity to experience the grandeur and natural beauty of the Rocky Mountains.

Elevation

The park is known for its high elevation, with elevations ranging from around 7,600 feet at the lowest point to over 14,000 feet at the summit of Longs Peak. The high elevation contributes to the park’s alpine environment and diverse ecosystems.

Alpine Tundra

The park features extensive alpine tundra, characterized by low-lying vegetation adapted to harsh conditions at high elevations. The alpine ecosystems are home to hardy plants, such as alpine forget-me-nots and cushion plants, as well as wildlife adapted to the challenging environment.

Mountain Peaks

Rocky Mountain National Park is home to over 60 mountain peaks exceeding 12,000 feet in elevation, with several exceeding 13,000 feet. Notable peaks include Longs Peak, which stands at 14,259 feet and is the highest point in the park.

Glacial Features

Glacial activity has shaped the landscape of Rocky Mountain National Park. U-shaped valleys, cirques, moraines, and glacial lakes are evidence of past glaciation. Glacier Gorge and Tyndall Gorge are examples of glacially-carved valleys in the park.

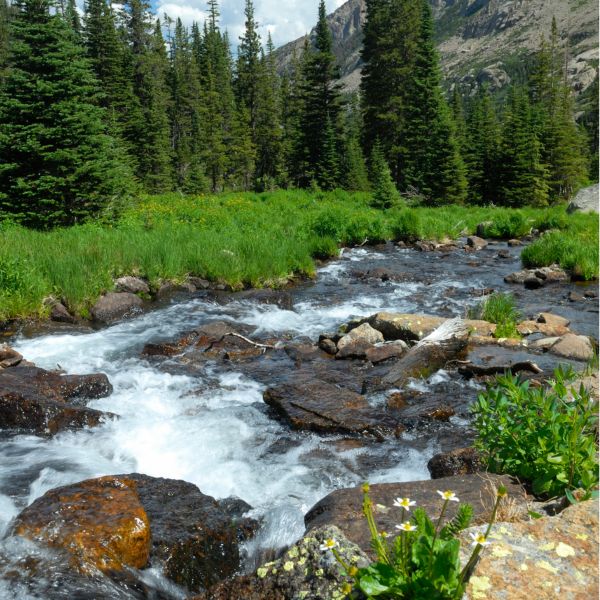

Rivers and Streams

The headwaters of several major rivers, including the Colorado River and the Cache la Poudre River, are located in the park. These rivers and their tributaries flow through rugged canyons and provide important habitats for aquatic life.

Forests

Lower elevations in the park are covered by dense forests, including subalpine and montane forests. Common tree species include spruce, fir, pine, and aspen. These forests provide habitat for a variety of wildlife, including elk, mule deer, and black bears.

Plants

Rocky Mountain National Park is home to a remarkable array of plant life adapted to its diverse montane and alpine ecosystems. The park’s flora includes a variety of species such as conifers, aspen trees, wildflowers, and alpine tundra plants, each uniquely adapted to the park’s rugged terrain and varying elevations. Visitors to Rocky Mountain National Park can explore the botanical wonders of the region, encountering a fascinating mix of plant species that contribute to the park’s natural beauty and ecological richness.

Animals

Mammals

Rocky Mountain National Park is home to a diverse array of mammals adapted to the varying elevations and ecosystems within the park. From large herbivores to elusive predators, the park’s mammalian residents contribute to its ecological richness.

Elk (Cervus canadensis): Elk are one of the most iconic mammals in the park. During the fall rut (mating season), male elk can be heard bugling, and visitors may witness dramatic displays of dominance.

Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus): Mule deer are commonly found in the park’s lower elevations. They are known for their large ears and distinctive bounding gait.

Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis): Bighorn sheep inhabit the steep, rocky terrain of the park. Visitors may observe these sure-footed animals navigating the cliffs and ledges.

Moose (Alces alces): Moose are occasionally seen in the park, particularly in wetland areas. Their large size and distinctive antlers make them a sought-after sight for wildlife enthusiasts.

Black Bear (Ursus americanus): Black bears are the most common bear species in the park. They are omnivores, feeding on a variety of plant materials, insects, and occasionally small mammals.

Mountain Lion (Puma concolor): Also known as cougars or pumas, mountain lions are elusive predators. Sightings are rare due to their solitary and nocturnal nature.

Coyote (Canis latrans): Coyotes are adaptable predators found in a variety of habitats within the park. They are often heard yipping and howling, especially during the evening.

Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes): Red foxes are well-adapted to the park’s diverse environments. They are opportunistic omnivores, feeding on small mammals, birds, and vegetation.

American Marten (Martes americana): Martens are small, agile carnivores that inhabit coniferous forests. They are primarily active during the night and are skilled climbers.

Yellow-Bellied Marmot (Marmota flaviventris): Marmots are large ground-dwelling rodents commonly seen in alpine and subalpine meadows. They are known for their distinctive whistling calls.

Beaver (Castor canadensis): Beavers are found in riparian areas, where they build dams and lodges. Their activities contribute to the shaping of wetland ecosystems.

Pika (Ochotona princeps): These small, rabbit-like mammals inhabit rocky talus slopes in the alpine zone. They are known for their distinctive “haypiles,” where they store vegetation for winter.

Reptiles

Birds

Fish

Amphibians

“Colorado is an oasis, an otherworldly mountain place.”

-Brandi Carlile

“The Rockies are the grandest country I ever saw.”

– John Wesley Powell

“Our peace shall stand as firm as rocky mountains.”

-William Shakespeare

“The Rockies are therefore very young and should never be thought of as ancient. They are still in the process of building and eroding, and no one today can calculate what they will look like ten million years from now. They have the extravagant beauty of youth, the allure of adolescence, and they are mountains to be loved.”

– James A. Michener